How do you know?

Acts 16: 9-15

New Ark United Church of Christ, Newark, DE

May 26, 2019

Do you remember your first paradigm shift? Doesn’t everyone? It happens to everyone sooner or later and hopefully over your whole lifetime. You had a firmly held, long-cherished belief or tradition or assumption but then your learning increased, your knowledge changed and you changed with it.

I recall one hot summer day when I was 7 years old. My younger brother and I were sitting on the front steps of our house with our babysitter. A young man walked past our house and took off his t-shirt as he went. I thought that’s a great idea. I would feel so much cooler if I took off my shirt too—the assumption being that there was no difference between myself and the young man. Just as I was about to remove my shirt, the babysitter stopped me and said, “You can’t do that. Boys can take off their shirts but girls can’t.” And I remember feeling mad about how unfair it was, which may have been the moment when I became a feminist.

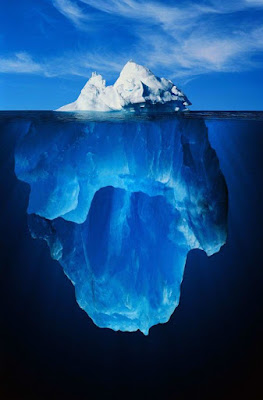

This is how human beings grow, how humanity evolves. Our paradigms shift. Once we thought the world was flat and that the sun revolved around the earth (which contradicts the flat earth theory, when you think about it). Once we thought we lived solely in a mechanical universe of cause and effect. Now we are beginning to realize that within the depth of this mechanical universe there is a quantum universe that operates differently than the universe we can observe with the naked eye. Health care is a right is a paradigm shift. Housing is a right is a paradigm shift. Black Lives Matter is a paradigm shift.

How do you know what you know? It’s one of the oldest philosophical questions. Mostly we know what we know through perception, through our experience, our senses, our thoughts and our feelings.

18th century public intellectual and philosopher David Hume wrote that we are nothing but a collection of different perceptions that are constantly changing, thus changing how we perceive ourselves and the world around us. He observed that we are more influenced by our feelings, our passions than by reason, and that if we could just accept this about ourselves and each other, both in our lives and in our life together, we would live more peacefully and be happier than if we denied it. We find an idea agreeable or threatening and on that basis, more than any other, we declare that idea to be true or false. Usually we use reason to support our viewpoint after we have decided we like or dislike an idea, after it makes sense to us. We change people’s minds not through reason but through feelings, connecting with people through things like empathy, reassurance, good example, encouragement, art and music.

Hume thought that what makes for good people is being raised with the art of decency through our emotions, with good habits of feeling. One can be rational, be able to follow a complicated argument, and yet be a person no one wants to be around, a person who is insensitive to the suffering of others, who believes the rules do not apply to them, or who cannot control their temper. And we all know someone like that, don’t we? How do we know good people when we meet them? By how we feel when we’re with them.

It’s not our brains or logic that tells us who God is or what God is but our hearts, our feelings:

There are some things

I may not know

There are some places

I cannot go

But I am sure

Of this one thing

That God is real

And I can feel

God deep in my soul

Yes God is real

Real in my soul

Yes God is real

For God has washed

And made me whole

God’s love for me

Is like pure gold

Yes God is real

For I can feel

God deep in my soul

Paul went to Macedonia based on a vision, on a feeling, on the idea that God was guiding him. Lydia was baptized and her whole household with her, not because Paul outlined a rational case for being a follower of Jesus, not because God opened her mind but her heart to listen, and she felt Paul’s words, his passion to be true. Paul and his companions stayed with Lydia at her home not because they read great reviews of her hospitality or because she questioned them until she was satisfied, but because she prevailed upon them—she wouldn’t take no for an answer. Lydia was eager to show her faithfulness in return for connection, community, perhaps even a deeper purpose to her life—providing hospitality out of her means.

In churchy language, how do you know what you know is known as the spiritual practice of discernment. How do we know what direction to take in our lives or as a congregation? How do we know we’ve experienced a call from God? How do we know if we’re on the verge of another paradigm shift, another challenge to our beliefs, traditions and assumptions about what it means to be Church? In the United Church of Christ, we say God is still speaking, with a deliberate comma placed after ‘speaking’ as a way of saying “we are listening for what’s next”.

What’s next for the Church? It’s an important question that we need to keep asking, and of course each of us has our own experience, ideas, and feelings about Church. Each of us has our own spiritual journey, a path unique to us, and yet we travel together. Much of our spiritual hunger is not about sharing the same beliefs but about shared values and experiences, shared feelings—about being mutually known and understood, being able to trust one another, as we love and serve together.

And yet we can’t always decide what is good about being Church, about serving and following Jesus based on how we feel about it. Love your enemies and pray for them, forgive seven times seventy, take up your cross and follow—none of these feel particularly good and yet how do we know these to be true, to be worthy of our trust? These ask us to do the hard work of love even when we don’t feel it, even when it’s not deserved. They challenge our assumptions, our beliefs, what we think we know.

Poet Wendell Berry wrote, “We have lived our lives by the assumption that what was good for us would be good for the world. We have been wrong. We must change our lives so that it will be possible to live by the contrary assumption, that what is good for the world will be good for us. And that requires that we make the effort to know the world and learn what is good for it.”

It’s not about being right or wrong but about what is good for the world. Not only about what feels real down deep in my soul or your soul but the soul of the whole world. It’s about more about listening, less about convincing others. It’s about what serves the dignity and worth of every living thing. The essence of the gospel is this: What is good for the most vulnerable and marginalized is good for all of us.

New Ark United Church of Christ, Newark, DE

May 26, 2019

I recall one hot summer day when I was 7 years old. My younger brother and I were sitting on the front steps of our house with our babysitter. A young man walked past our house and took off his t-shirt as he went. I thought that’s a great idea. I would feel so much cooler if I took off my shirt too—the assumption being that there was no difference between myself and the young man. Just as I was about to remove my shirt, the babysitter stopped me and said, “You can’t do that. Boys can take off their shirts but girls can’t.” And I remember feeling mad about how unfair it was, which may have been the moment when I became a feminist.

This is how human beings grow, how humanity evolves. Our paradigms shift. Once we thought the world was flat and that the sun revolved around the earth (which contradicts the flat earth theory, when you think about it). Once we thought we lived solely in a mechanical universe of cause and effect. Now we are beginning to realize that within the depth of this mechanical universe there is a quantum universe that operates differently than the universe we can observe with the naked eye. Health care is a right is a paradigm shift. Housing is a right is a paradigm shift. Black Lives Matter is a paradigm shift.

How do you know what you know? It’s one of the oldest philosophical questions. Mostly we know what we know through perception, through our experience, our senses, our thoughts and our feelings.

18th century public intellectual and philosopher David Hume wrote that we are nothing but a collection of different perceptions that are constantly changing, thus changing how we perceive ourselves and the world around us. He observed that we are more influenced by our feelings, our passions than by reason, and that if we could just accept this about ourselves and each other, both in our lives and in our life together, we would live more peacefully and be happier than if we denied it. We find an idea agreeable or threatening and on that basis, more than any other, we declare that idea to be true or false. Usually we use reason to support our viewpoint after we have decided we like or dislike an idea, after it makes sense to us. We change people’s minds not through reason but through feelings, connecting with people through things like empathy, reassurance, good example, encouragement, art and music.

Hume thought that what makes for good people is being raised with the art of decency through our emotions, with good habits of feeling. One can be rational, be able to follow a complicated argument, and yet be a person no one wants to be around, a person who is insensitive to the suffering of others, who believes the rules do not apply to them, or who cannot control their temper. And we all know someone like that, don’t we? How do we know good people when we meet them? By how we feel when we’re with them.

It’s not our brains or logic that tells us who God is or what God is but our hearts, our feelings:

There are some things

I may not know

There are some places

I cannot go

But I am sure

Of this one thing

That God is real

And I can feel

God deep in my soul

Yes God is real

Real in my soul

Yes God is real

For God has washed

And made me whole

God’s love for me

Is like pure gold

Yes God is real

For I can feel

God deep in my soul

Paul went to Macedonia based on a vision, on a feeling, on the idea that God was guiding him. Lydia was baptized and her whole household with her, not because Paul outlined a rational case for being a follower of Jesus, not because God opened her mind but her heart to listen, and she felt Paul’s words, his passion to be true. Paul and his companions stayed with Lydia at her home not because they read great reviews of her hospitality or because she questioned them until she was satisfied, but because she prevailed upon them—she wouldn’t take no for an answer. Lydia was eager to show her faithfulness in return for connection, community, perhaps even a deeper purpose to her life—providing hospitality out of her means.

In churchy language, how do you know what you know is known as the spiritual practice of discernment. How do we know what direction to take in our lives or as a congregation? How do we know we’ve experienced a call from God? How do we know if we’re on the verge of another paradigm shift, another challenge to our beliefs, traditions and assumptions about what it means to be Church? In the United Church of Christ, we say God is still speaking, with a deliberate comma placed after ‘speaking’ as a way of saying “we are listening for what’s next”.

What’s next for the Church? It’s an important question that we need to keep asking, and of course each of us has our own experience, ideas, and feelings about Church. Each of us has our own spiritual journey, a path unique to us, and yet we travel together. Much of our spiritual hunger is not about sharing the same beliefs but about shared values and experiences, shared feelings—about being mutually known and understood, being able to trust one another, as we love and serve together.

And yet we can’t always decide what is good about being Church, about serving and following Jesus based on how we feel about it. Love your enemies and pray for them, forgive seven times seventy, take up your cross and follow—none of these feel particularly good and yet how do we know these to be true, to be worthy of our trust? These ask us to do the hard work of love even when we don’t feel it, even when it’s not deserved. They challenge our assumptions, our beliefs, what we think we know.

Poet Wendell Berry wrote, “We have lived our lives by the assumption that what was good for us would be good for the world. We have been wrong. We must change our lives so that it will be possible to live by the contrary assumption, that what is good for the world will be good for us. And that requires that we make the effort to know the world and learn what is good for it.”

It’s not about being right or wrong but about what is good for the world. Not only about what feels real down deep in my soul or your soul but the soul of the whole world. It’s about more about listening, less about convincing others. It’s about what serves the dignity and worth of every living thing. The essence of the gospel is this: What is good for the most vulnerable and marginalized is good for all of us.

Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment