Love and science

Luke 10:25-28

Craigville Colloquy Opening Worship

July 8, 2019

First I have to make a confession. Well, really it’s a disclaimer dressed up as a confession. The last time I spoke like this at Colloquy—in 2002 I presented a paper entitled “The Physics of the Body of Christ”—I was declared a heretic. Preaching about faith and science to a room full of faithful church folx, theologians and scientists makes me feel like I have to get it right. I am a poet, an artist, and a dreamer who loves metaphor. If I misuse anyone’s language or terms I know that there will be hell to pay and a lecture followed by a pop quiz. So let me just remind us of the wisdom given to us by George Box: All models are wrong. Some are useful or helpful. I offer this message in the hope that it will be helpful.

Two summers ago I read Dan Brown’s newest novel, Origin. It’s another thrilling page turner that pretty much parallels the plot structure of The Da Vinci Code. One surprising quote that came from it was this: “Love is not a finite emotion. We don’t have only so much to share. Our hearts create love as we need it.” And yet in the stories Dan Brown writes, there is little love for religion or the religious establishment. Origin is yet another installment of that trope.

One of the characters in Origin is an actual person: MIT professor and biophysicist Jeremy England. England, his work and his theories are used, in his words, as “a prop for a billionaire futurist whose mission is to demonstrate that science has made God irrelevant”. England, an Orthodox Jew, finds this interesting, given that there’s no real science in the book. So even though my idea for this message sprang from a somewhat fictional character whose theory about the purpose of the universe, of energy and matter is oversimplified, I think the idea still warrants attention.

The oversimplified theory of the purpose of the universe is to disperse, to spread energy. The universe is constructed of dissipative structures – collections of molecules organized to better disperse energy. And what does dissipative mean but to be prodigal: wastefully extravagant, profligate. Buddhism and the principle of impermanence remind us: “All those who are born will die. All that is gathered will disperse. All meetings will end in separation. Understanding this is the beginning of freedom.” Snowflakes are designed to melt. Stars eventually burn through their hydrogen and helium. Lightning bolts disperse the energy of a thunderstorm.

If this is how things are supposed to work, a cycle of energy into matter into energy, then in theological terms, plastic is our original sin. In its many forms, plastic locks up that energy and holds onto it for hundreds of years. All of the data I’m about to tell you comes from a study done by industrial ecologist Roland Geyer and researchers Jenna Jambeck and Kara Lavender Law. Human beings have made over 8 billion metric tons of plastic since 1950. About 30% of all the plastic ever made is still in use. Of the rest of it, 79% of it is in landfills and the environment, like oceans, rivers and lakes and the wildlife that live in those habitats. 12% of it is incinerated. Only 9% of plastic is recycled. Over time we’ve thrown out over 6 billion metric tons of plastic and we’re still living with nearly all of it. A lot of our plastic waste is sent to poorer countries—under the rug where we can’t see it. It normally takes about 80 to 100 years for a healthy human being to disperse their all of their energy, that is, to live and then to die. For plastic to disperse its energy it will take anywhere from 400 to 1000 years. Half of the plastic made since 1950 was made in the last 13 years.

We want to keep what we have, all of it. And yet to disperse energy, we can’t possibly keep what we have. We want the beauty and purity of nature and all its creatures and we want convenience. We want clean water and clean air and we want the independence of our car culture. We want to bring order to chaos without the price that it brings.

Environmental lawyer and activist Gus Speth said, “I used to think the top environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and climate change. I thought that with 30 years of good science we could address those problems. But I was wrong. The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed, and apathy…and to deal with those we need a spiritual and cultural revolution. And we scientists don’t know how to do that.” And that is one of the biggest spiritual problems: how to disperse energy that we’d rather hold on to. It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom. If you have two coats, give one away. Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.

The Body of Christ—broken and poured out for all—is also a way to disperse energy. Energy that looks like justice. Energy that looks like liberation. Energy that looks like wholeness. Energy that looks like sacrifice. Energy that looks like self-gift. Energy that looks like compassion. And yet we who are hands and feet, and mind and heart, soul and strength that is the Body of Christ—we too want to keep what we have because we’re human. We want to keep what we have because we’re addicted to the way things are.

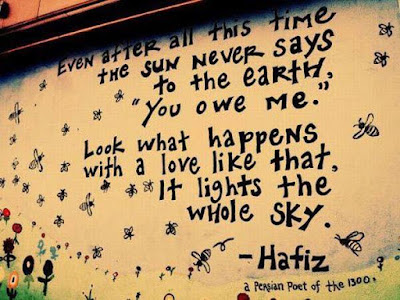

If you’re familiar with the 12 steps, one piece of wisdom regarding the 4th step—a personal and moral inventory—says “Consider how hard it is to change yourself and you’ll understand what little chance you have in trying to change others.” And yet that is the spiritual transformation—to be the change you wish to see in the world. The kingdom of God is within you and among you. Love is patient and kind. Love does not insist on its own way. Love is not a finite emotion. We don’t have only so much to share. Our hearts create love as we need it. And as others need it.

If self-interest—to keep what we have—is our stumbling block, then to love one’s neighbor as ourselves means our neighbor’s highest good is just as important, if not more so, than ours. And who is our neighbor but the one whose need is even greater than ours?

The hard work and the inconvenience of good science and great love—love that is willing to lay down life for friends and neighbors—I believe that is our prayer, that is our hope, and that is our calling.

Craigville Colloquy Opening Worship

July 8, 2019

First I have to make a confession. Well, really it’s a disclaimer dressed up as a confession. The last time I spoke like this at Colloquy—in 2002 I presented a paper entitled “The Physics of the Body of Christ”—I was declared a heretic. Preaching about faith and science to a room full of faithful church folx, theologians and scientists makes me feel like I have to get it right. I am a poet, an artist, and a dreamer who loves metaphor. If I misuse anyone’s language or terms I know that there will be hell to pay and a lecture followed by a pop quiz. So let me just remind us of the wisdom given to us by George Box: All models are wrong. Some are useful or helpful. I offer this message in the hope that it will be helpful.

Two summers ago I read Dan Brown’s newest novel, Origin. It’s another thrilling page turner that pretty much parallels the plot structure of The Da Vinci Code. One surprising quote that came from it was this: “Love is not a finite emotion. We don’t have only so much to share. Our hearts create love as we need it.” And yet in the stories Dan Brown writes, there is little love for religion or the religious establishment. Origin is yet another installment of that trope.

One of the characters in Origin is an actual person: MIT professor and biophysicist Jeremy England. England, his work and his theories are used, in his words, as “a prop for a billionaire futurist whose mission is to demonstrate that science has made God irrelevant”. England, an Orthodox Jew, finds this interesting, given that there’s no real science in the book. So even though my idea for this message sprang from a somewhat fictional character whose theory about the purpose of the universe, of energy and matter is oversimplified, I think the idea still warrants attention.

The oversimplified theory of the purpose of the universe is to disperse, to spread energy. The universe is constructed of dissipative structures – collections of molecules organized to better disperse energy. And what does dissipative mean but to be prodigal: wastefully extravagant, profligate. Buddhism and the principle of impermanence remind us: “All those who are born will die. All that is gathered will disperse. All meetings will end in separation. Understanding this is the beginning of freedom.” Snowflakes are designed to melt. Stars eventually burn through their hydrogen and helium. Lightning bolts disperse the energy of a thunderstorm.

If this is how things are supposed to work, a cycle of energy into matter into energy, then in theological terms, plastic is our original sin. In its many forms, plastic locks up that energy and holds onto it for hundreds of years. All of the data I’m about to tell you comes from a study done by industrial ecologist Roland Geyer and researchers Jenna Jambeck and Kara Lavender Law. Human beings have made over 8 billion metric tons of plastic since 1950. About 30% of all the plastic ever made is still in use. Of the rest of it, 79% of it is in landfills and the environment, like oceans, rivers and lakes and the wildlife that live in those habitats. 12% of it is incinerated. Only 9% of plastic is recycled. Over time we’ve thrown out over 6 billion metric tons of plastic and we’re still living with nearly all of it. A lot of our plastic waste is sent to poorer countries—under the rug where we can’t see it. It normally takes about 80 to 100 years for a healthy human being to disperse their all of their energy, that is, to live and then to die. For plastic to disperse its energy it will take anywhere from 400 to 1000 years. Half of the plastic made since 1950 was made in the last 13 years.

We want to keep what we have, all of it. And yet to disperse energy, we can’t possibly keep what we have. We want the beauty and purity of nature and all its creatures and we want convenience. We want clean water and clean air and we want the independence of our car culture. We want to bring order to chaos without the price that it brings.

Environmental lawyer and activist Gus Speth said, “I used to think the top environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse, and climate change. I thought that with 30 years of good science we could address those problems. But I was wrong. The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed, and apathy…and to deal with those we need a spiritual and cultural revolution. And we scientists don’t know how to do that.” And that is one of the biggest spiritual problems: how to disperse energy that we’d rather hold on to. It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom. If you have two coats, give one away. Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.

The Body of Christ—broken and poured out for all—is also a way to disperse energy. Energy that looks like justice. Energy that looks like liberation. Energy that looks like wholeness. Energy that looks like sacrifice. Energy that looks like self-gift. Energy that looks like compassion. And yet we who are hands and feet, and mind and heart, soul and strength that is the Body of Christ—we too want to keep what we have because we’re human. We want to keep what we have because we’re addicted to the way things are.

If you’re familiar with the 12 steps, one piece of wisdom regarding the 4th step—a personal and moral inventory—says “Consider how hard it is to change yourself and you’ll understand what little chance you have in trying to change others.” And yet that is the spiritual transformation—to be the change you wish to see in the world. The kingdom of God is within you and among you. Love is patient and kind. Love does not insist on its own way. Love is not a finite emotion. We don’t have only so much to share. Our hearts create love as we need it. And as others need it.

If self-interest—to keep what we have—is our stumbling block, then to love one’s neighbor as ourselves means our neighbor’s highest good is just as important, if not more so, than ours. And who is our neighbor but the one whose need is even greater than ours?

The hard work and the inconvenience of good science and great love—love that is willing to lay down life for friends and neighbors—I believe that is our prayer, that is our hope, and that is our calling.

Comments

Post a Comment