The untied Church

New Ark United Church of Christ, Newark, DE

August 16, 2020Unity is messy. In fact, it’s more than that. It’s painful and costly, often at human expense, especially the most vulnerable and those the powerful deem unworthy of their humanity. We have yet to achieve any kind of lasting unity without the use of coercion, manipulation, or force, which then isn’t really unity but the imposition of power. Neither is unity achieved solely by possessing a common enemy or threat or even a higher purpose. To some degree we all have within us competing goals of self-interest and the common good. There are days it can be difficult to find unity even within ourselves.

So when the psalmist says how good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity, it’s a dream, a hope, a fervent prayer. Psalm 133 is one of the Songs of Ascent that pilgrims would sing as they made their way up the temple mount in Jerusalem. It’s also sung on Friday evenings as part of the Shabbat celebration.

Hineh mah tov umah nayim, shevet achim gam yachad

Hineh mah tov umah nayim, shevet achim gam yachad

|

| Psalm 133, Ben Shahn, 1963 |

And yet there’s a story here. The Hebrew word achim in non-inclusive language translates as brothers or kinsmen. Just about every set of brothers mentioned in the Bible hardly ever lived in unity: Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau, Joseph and his brothers who sold him into slavery, then Joseph threw them into prison the next time he saw them.

Aaron is the older brother of Moses. The two of them along with their sister Miriam led God’s people out of Egypt and through the wilderness to reach the Promised Land. It was Aaron the people went to when Moses delayed coming down from the mountain and his confab with God. Though Aaron may have been Moses’ mouthpiece and thus, God’s, it was Moses the people wanted, and having to wait for him, they grew anxious and decided to give up on him. They demanded that Aaron produce gods for the people so they could get on the road and keep going. Instead of saying, no don’t do that or let’s give Moses five more minutes or could I take a message, Aaron gave into them. He collected their gold jewelry and melted it down to make a golden calf and said “Here are your gods, O Israel! Now let’s party!”

As you can imagine this did not sit well with God. Moses had to step in and talk down the One who made heaven and earth from turning Aaron and everyone else into a smoldering ash heap. And yet by the time we get from Exodus to Leviticus, Aaron is anointed as high priest, hence, the precious oil running down his head onto his beard and the collar of his robes. Aaron is not only consecrated for service to God but with great extravagance. One who had earned God’s wrath now serves with God’s blessing.

As for the dew of Mt. Hermon falling on the mountains of Zion, Hermon was the great mountain of the northern kingdom while Zion was in the southern kingdom, in Jerusalem. After the reign of King Solomon, God’s people split into north and south; there would be no possibility of unity for several hundred years. The north was lush while the south was dry. This is a verse about sharing and receiving. Unity is possible when abundance shares rather than hoards, when the one with power yet in need receives with welcome, when both put aside self-interest and past grievances to achieve wholeness, shalom, for everyone.

And it is here—in the midst of imperfection and hurt feelings, broken promises and contentious people—that God ordains God’s blessing: life forevermore. And this life, this blessing isn’t individualistic but communal: from our kindred, our families, whether it’s the one we’re born into or the one we choose, to the communities we live in, to the repair of entire nations.

Unity doesn’t come from majority rule. Unity isn’t a zero-sum, winner-take-all game. One of the unique aspects of this church is our commitment to achieve consensus when we make decisions about our life together. Consensus doesn’t mean we all agree but rather we work toward finding solutions that we can all actively support or at least we can live with. It also means that sometimes it takes a while before a decision is made. For people in pain who need justice it can be excruciating, and so we need to be mindful of those whose justice delayed is justice denied. For people who like efficiency, who like to get things done, consensus can feel glacial as opposed to taking a vote. But it’s an efficiency of another kind—an efficient use of that blessing, life forevermore, life not lived solely for oneself or one’s own but lived in community.

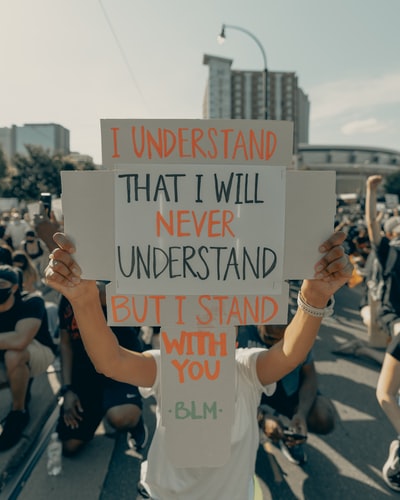

In the words of T.S. Eliot, “What life have you if you have not life together? There is no life that is not in community, and no community not lived praise of God.” Community is messy. It’s an evolution. It’s long term work. Sometimes it needs reformation, sometimes it needs revolution. We can be lulled into mistaking unity for the status quo but vibrant community is anything but static. Episcopal bishop Mark Dyer proposes that every 500 years or so we live through an upheaval in which we question our structures and institutions, a rummage sale of sorts out of which we decide what we will keep and what we will dispose of. And it looks like racism, patriarchy, and empire are finally on the table. But so are democracy, communal care, and the will toward the good of all, so zealous are some to burn it all down.

Out of this upheaval the question that must be satisfied is “By what authority shall we live?” Those who are still playing the zero-sum game want to dictate the rules and are moving closer to declaring unity by fiat, testing the waters of authoritarianism and even fascism. There are some who still think the Church has an authority of a sort but the institution and structure and even its witness have been so entangled with racism and patriarchy and empire that we’ve become our own blind spot to the harm we do even as we try to do justice and make peace.

But that doesn’t mean we stop being Church. It means we have a lot of work to do. It means white cisgender heterosexual Jesus has got to go, which means we need to start paying attention to Black and brown, Asian and Native, womanist and queer and transgender theologies and experiences that we would unlearn and de-center whiteness and everything that goes with it. Like the dew of Mt. Hermon, like that precious oil running down—not trickling—it means not only divesting ourselves of our wealth and investing it those marginalized communities but a reordering of our economy. “The rich are sent away empty and the poor are filled with good things.” It means untying ourselves from systems of power and control and continuing the painstaking work of consensus and trust-building and relationships.

It is in this difficult place, in the mess that hopefully will one day become a more perfect union that actually does promote the general welfare, that God ordains blessing, life forevermore. God doesn’t need us to be ‘nice people’; the world doesn’t need us to be nice people but rather people who will no longer dominate; no longer a people who take. But it begins with us and our resolve to not give up on that fervent prayer: that indeed how good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity.

Out of this upheaval the question that must be satisfied is “By what authority shall we live?” Those who are still playing the zero-sum game want to dictate the rules and are moving closer to declaring unity by fiat, testing the waters of authoritarianism and even fascism. There are some who still think the Church has an authority of a sort but the institution and structure and even its witness have been so entangled with racism and patriarchy and empire that we’ve become our own blind spot to the harm we do even as we try to do justice and make peace.

|

| Images of Christ, David Hayward, nakedpastor.com |

It is in this difficult place, in the mess that hopefully will one day become a more perfect union that actually does promote the general welfare, that God ordains blessing, life forevermore. God doesn’t need us to be ‘nice people’; the world doesn’t need us to be nice people but rather people who will no longer dominate; no longer a people who take. But it begins with us and our resolve to not give up on that fervent prayer: that indeed how good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity.

Amen.

A virtual choir of 17,572 voices from 129 countries.

A virtual choir of 17,572 voices from 129 countries.

Benediction – enfleshed.com

Faithful ones,

the grace of God goes with us into the messiness of life,

extending to us peace in the midst of what is unfinished, untidy, unclear, or unresolved.

With steadfast patience,

let us go from here encouraged in the labors of love,

pressing on through complexities,

and staying present to the troubles that call for our attention –

within us, between us, and around us.

Blessed be our journeys of healing and transformation.

Faithful ones,

the grace of God goes with us into the messiness of life,

extending to us peace in the midst of what is unfinished, untidy, unclear, or unresolved.

With steadfast patience,

let us go from here encouraged in the labors of love,

pressing on through complexities,

and staying present to the troubles that call for our attention –

within us, between us, and around us.

Blessed be our journeys of healing and transformation.

Comments

Post a Comment