Changing the story

Luke 3: 15-17, (18-20), 21-22

New Ark United Church of Christ, Newark, DE

January 9, 2022

You’ve probably heard the statistic that most people can be in relationship with and/or be acquainted with about 150 people. Most organizations, family businesses, communities and such of this size can exist without hierarchies or titles to function without too many problems. They can be more loosely organized and be guided by personal knowledge and relationships rather than a board of directors. When an organization or a community grows beyond that number, more often than not it must reinvent itself, add more structure and policies, or it can become unwieldy.

In his book Sapiens, about the history and development of humanity, Yuval Noah Harari writes that in order for human beings to eventually create cities and empires of millions of people, what made the difference was and is shared stories, paradigms, and myths. Strangers can come together in a group and accomplish a goal when they share common beliefs, laws, heritage, symbols, and history. Over centuries these stories have been interwoven into a complex web of constructs and as such carry a great deal of power, to a point that often we do not question them or their existence.

How we grow, how we change by what means we cooperate, is by changing the story; literally, the words that create the story become flesh and live among us. Harari gives the example of the French Revolution, how an entire nation made the incredible pivot from the divine right of kings to the sovereignty of the people, almost overnight. Telling a convincing story carries enormous power. It can enable millions of people to change behaviors, affect how we work together, shape our values and our ability to achieve what we want.

The author of the gospel of Luke changed the story of Jesus as it was known in the gospel of Mark, not just by filling in gaps, like the Christmas story but by changing the intent of the story itself. The gospel of Mark was written in haste or at least in hasty language, to get the story down as all hell was breaking loose in Jerusalem, as Rome came down hard on those who tried to subvert their control. Mark’s gospel sought to give direction and hope that God is on the side of the oppressed and that the kingdom of God is at hand. Luke’s gospel was written more for those who were not part the covenant with Israel. And so right at the get-go with John the Baptist we have a question not asked in the baptism story in Mark: “Are you the Messiah?” John neither confirms nor denies if he is the Messiah, then points the crowd toward the one who will baptize with fire and with the Holy Spirit, toward Jesus.

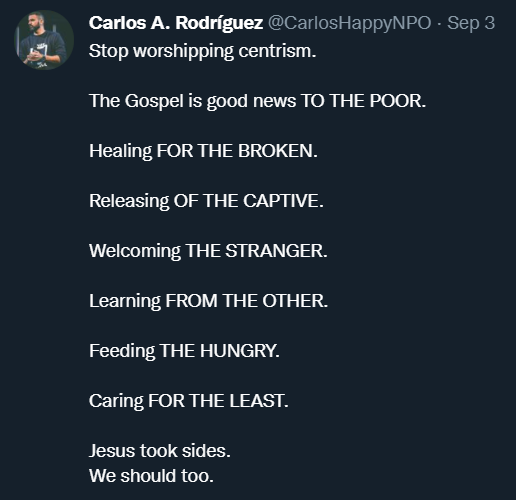

Here the story changes from Jewish messianic hopes to the hope of one who will save any who are oppressed. Luke portrays Jesus as Son of God versus the emperor who was also called Son of God, a political title rather than a theological one, the Prince of Peace versus the one whose power was based on war and violence. While the gospel of Matthew tries to draw a discernable line between the covenant with Israel and Jesus of Nazareth, Luke takes the message of Jesus to those who were treated as outsiders: the poor, women, children, shepherds and Samaritans.

One of the dangers of changing the story is when the story change is depicted as better than, an improvement over the preceding story, when the story change is weaponized against the original, on-going story. Old Covenant vs. New Covenant. Old Testament God vs. New Testament God. It’s called supercessionism, also called replacement theology, in which the covenant through Jesus not only fulfills but replaces the covenant made with Moses. Religious history begins to sound more like a nasty, vicious divorce in which those who follow Jesus blame not just a few leaders in the religious establishment but all Jews for the death of Jesus. Never mind that Jesus was himself Jewish, that it was the Roman Empire that executed him, that the Church owes its survival to empire, and that the Church is responsible for centuries of anti-Semitism.

And so, I try to be very careful in Advent when prophets like Isaiah speak about the hope of the people waiting for rescue to not connect that hope specifically to Jesus of Nazareth. I don’t think we can sing “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel” with integrity, because the Church is not, nor has it really ever been, “captive Israel mourning in lonely exile”. That’s the story of Jesus’ ancestors but as people of privilege it’s not our story to claim as our own.

There’s another story we’ve been led to believe, that there can only be one story, one true story, and that it is the story of the winners. It goes something like this. Different stories cannot exist side by side. Stories compete for the truth rather than contribute to the truth. Rather than change the story we must control the narrative, like Herod throwing John the Baptist in prison.

We are living through just such a time, a crucial struggle between changing the story and controlling the narrative. The messaging of how to handle the pandemic is but a symptom of the problem. There are some who have been calling for scrutiny of our nation’s history, to honestly examine and shed light on those parts of our story that caused generational trauma from enslavement, colonization, and genocide—and there those who are violently opposed to any other version of the story besides the one we pretended was true. There are still those who not only believe in the Big Lie but are actively organizing because of it, who would rather suppress the will of the people, who would rather deny liberty to all and burn down the American experiment than admit to the treasonous crime of an insurrection and allow the story to change.

From the #MeToo movement to reproductive justice to Black Lives Matter to queer and transgender rights to the Poor People’s Campaign to gun violence prevention to mental health advocacy and so much more, it’s about whose story is listened to, believed, and trusted, whose story is empowered, whose story leads us forward. It is the responsibility, the role of every generation to change the story, to make it their story. Some of those stories require a change in grammar, in pronouns so their story is told authentically, with integrity, and it is up to us to create that courageous space so that their story may be told and lived alongside all the other stories. The stories that need to be heard require Whiteness to take a backseat and for patriarchy to be smashed, for kindom on earth and empire to end. These stories require people to be more valuable than property, compassion more abundant than hoarded wealth, and the earth more important than profit shares.

42 years ago three small worshiping communities banded together and changed the story of how they would be church, how they would live out the Jesus story. That choice is before us every day: how will we embody, enflesh the Jesus story of fearless compassion, radical forgiveness, restorative justice, unconditional love, in our time, with who we are.

And if we allow it, it is a story that will change us. For good. Amen.

Benediction – based on a prayer by Gina Kohlhelpp

Jesus, as we follow in your way,

make us a channel of your disturbance.

Where there is apathy, let us provoke,

Where there is silence, may we be a voice,

Where there is too much comfort,

and too little action,

Grant disruption.

Where there are doors closed

and hearts locked,

Grant us the willingness to listen.

When laws dictate and pain is overlooked,

When tradition speaks

louder than need,

Disturb us,

Teach us to be radical,

Grant that we may seek

to do justice than to talk about it;

To be with, as well as for, the poor;

To love the unlovable as well as the lovely;

To touch your passion, Jesus, in the

Pain of those we meet;

To accept responsibility to be church.

Make us a channel of your disturbance.

Amen.

Comments

Post a Comment