Wound care

Luke 6: 27-38

New Ark United Church of Christ, Newark, DE

February 20, 2022

I think this is one of the most misunderstood, romanticized, troublesome passages in the four gospels. We love it, we hate it or both; we admire it, aspire to it, wonder about it, struggle with it, resist it, question it. Some years ago, there was introduced a widespread interpretation of “turn the other cheek” that described being struck on the right cheek with the back of the hand, which in the 1st century was used to humiliate and insult someone of lower status: master to slave, husband to wife, parents to children, Romans to everyone else. To turn the other cheek would mean to be struck by an open hand or a fist, which was a tactic used by equals. Turning the other cheek was intended as an act of resistance against one’s oppressor, a refusal to be humiliated.

The same is true for giving up one’s cloak or coat or shirt or being pressed to carry a burden for a mile to then go two miles—Roman soldiers could harass locals into service but to do more than what was required was an act of resistance. Often attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt, it has been said that no one can make you feel inferior without your consent, regardless of how they treat you. But Jesus is instilling more than self-respect or inner strength, he is teaching non-violence.

When Jesus says, “love your enemies”, this is not collective pride at stake. The Greek word for enemy is a personal hatred, someone who seeks to do you harm. It is not systemic abuse or exploitation of a whole people, but the humiliation inflicted on and suffered by anyone who is on the bottom of society. Giving to anyone who begs is a reminder that almsgiving is a required spiritual practice, that begging is more humiliating than being begged of, and that the poor are God’s chief concern and thus, ours as well. God shows mercy and kindness to the oppressed but also to the ungrateful and the wicked. God as punisher of the wicked but merciful to everyone else turns God into a manipulative monster.

And yet what about those who have been abused or wronged? What about those who are constantly misgendered, called slurs, denied agency and rights? Should they love their enemy? Should someone being verbally abused as they enter Planned Parenthood love their enemy? Should a Black teenager cuffed and arrested for a fight with a White teenager, who was not detained, love their enemy? What about those who have been kicked out of their homes, their families because of who they are? What about those who have had to cut off ties with their families because of the wounds they have suffered?

A young Black man who I follow on Twitter was abused as a youth. He wrote that if there’s one thing he honestly wants God to do for him, it would be for God to punish every single person who has hurt him, abused him, those who have been nasty to him. But then he remembers he’s supposed to love your enemies and all that [stuff]. He says if he were to be frank, he can’t love his enemies. He can’t love those who hurt him without cause. He doesn’t just want God’s favor and mercy. He wants God’s vindication. He says, “I won’t accept anything less, even [despite] my hatred towards the ones who hurt me.” He’s also afraid to confess any of his pain, to talk to God honestly, bravely about the profound hurt and anger in his heart for fear that God will be angry toward him. Not only has he suffered physical and verbal abuse, but he has also suffered spiritual abuse. His need for justice, for vindication is also a need for healing, for wholeness. His wounds are deep and grievous and need care. He is in no shape to turn the other cheek.

I have no idea what it is like to be young and Black and male in this country. I have no idea what it is like to be transgender or queer or poor. I have no idea what it is like to live with chronic pain or with a disability. I have no idea what it is like to be oppressed. I have no idea what it is like to live with such pain and anger. Though it often does not serve any purpose to compare suffering, my wounds are not a result of the abuse of my identity, of who I am as a person. And I have privilege that affords me the resources for healing. The ability to love one’s enemies is connected to the time and space to heal, to transform pain, trauma, and anger into something we can live with, and there are too many people who have not had, who do not have what they need to heal from pain and trauma.

Anglican priest Rev. Daniel Brereton says that those who preach should preach from their scars and not their wounds. The same is true when it comes to loving our enemies. We can only love our enemies from our scars, not our wounds. Those who have been wronged and repeatedly so cannot be expected to love their enemies, to love and forgive from a place of pain and woundedness, a place of injustice. That only subjects those who are suffering to further injury, makes them vulnerable to those who wounded them, and increases their trauma.

If it is one thing the Church is called to do, it is to have compassion, to care for the wounded, especially those who have been wronged and excluded by community, those who are on the fringes of community, who have been hurt by community, including the Church. And yet if we are to be agents of healing, we need to attend to our own healing first. Lori Deschene, founder of the online community Tiny Buddha, writes, “Be the person who breaks the cycle. If you were judged, choose understanding. If you were rejected, choose acceptance. If you were shamed, choose compassion. Be the person you needed when you were hurting, not the person who hurt you. Vow to be better than what broke you—to heal instead of becoming bitter so you can act from your heart, not your pain.”

Poet Hana Malik wrote, “Forgiveness is taking the knife out of your back and not using it to hurt anyone else, no matter how much they hurt you.” Wound care is about not transferring our pain to anyone else, not using it as a force for revenge or power over others. If we cannot desire good for those who have hurt us, we can at least wish them no harm, not only for them but for our own good as well.

We live in a world permeated by trauma, generations of it, much of it ignored, devalued, and untreated. We live in a society that tells us to just move on and leave the past behind or keep the pain alive, in the present for as long as you can. Build monuments to your pain. Numb your pain. We are in danger of becoming the very thing we fight against. We would rather turn against each other than turn the other cheek. Jesus would rather we act from our heart, not our pain. Seek justice, yes, but not revenge. Weep and get angry and feel the sadness but not as a means of keeping wounds open as a source of power or control. We won't do this perfectly. It's messy and complicated. The awful, terrible, amazing thing about love is that it can both hurt and heal, it can make us vulnerable and strong, it is a weakness and it is a force, it can reduce us and it can resurrect us. Choose love anyway. Amen.

Benediction – Harold Warheim

Because the world is poor and starving,

Go with bread.

Because the world is filled with fear,

Go with courage.

Because the world is in despair,

Go with hope.

Because the world is living lies,

Go with truth.

Because the world is sick with sorrow,

Go with joy.

Because the world is weary of wars,

Go with peace.

Because the world is seldom fair,

Go with justice.

Because the world is under judgment,

Go with mercy.

Because the world will die without it,

Go with love.

New Ark United Church of Christ, Newark, DE

February 20, 2022

|

| Two hands holding each other, one with white skin, one with brown skin and a gold band on the ring finger, resting on a leg clothed in blue denim. |

I think this is one of the most misunderstood, romanticized, troublesome passages in the four gospels. We love it, we hate it or both; we admire it, aspire to it, wonder about it, struggle with it, resist it, question it. Some years ago, there was introduced a widespread interpretation of “turn the other cheek” that described being struck on the right cheek with the back of the hand, which in the 1st century was used to humiliate and insult someone of lower status: master to slave, husband to wife, parents to children, Romans to everyone else. To turn the other cheek would mean to be struck by an open hand or a fist, which was a tactic used by equals. Turning the other cheek was intended as an act of resistance against one’s oppressor, a refusal to be humiliated.

The same is true for giving up one’s cloak or coat or shirt or being pressed to carry a burden for a mile to then go two miles—Roman soldiers could harass locals into service but to do more than what was required was an act of resistance. Often attributed to Eleanor Roosevelt, it has been said that no one can make you feel inferior without your consent, regardless of how they treat you. But Jesus is instilling more than self-respect or inner strength, he is teaching non-violence.

When Jesus says, “love your enemies”, this is not collective pride at stake. The Greek word for enemy is a personal hatred, someone who seeks to do you harm. It is not systemic abuse or exploitation of a whole people, but the humiliation inflicted on and suffered by anyone who is on the bottom of society. Giving to anyone who begs is a reminder that almsgiving is a required spiritual practice, that begging is more humiliating than being begged of, and that the poor are God’s chief concern and thus, ours as well. God shows mercy and kindness to the oppressed but also to the ungrateful and the wicked. God as punisher of the wicked but merciful to everyone else turns God into a manipulative monster.

And yet what about those who have been abused or wronged? What about those who are constantly misgendered, called slurs, denied agency and rights? Should they love their enemy? Should someone being verbally abused as they enter Planned Parenthood love their enemy? Should a Black teenager cuffed and arrested for a fight with a White teenager, who was not detained, love their enemy? What about those who have been kicked out of their homes, their families because of who they are? What about those who have had to cut off ties with their families because of the wounds they have suffered?

|

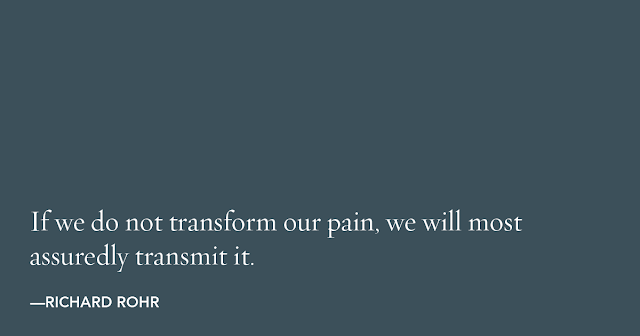

| Quote by Fr. Richard Rohr: "If we do not transform our pain, we will most assuredly transmit it." |

A young Black man who I follow on Twitter was abused as a youth. He wrote that if there’s one thing he honestly wants God to do for him, it would be for God to punish every single person who has hurt him, abused him, those who have been nasty to him. But then he remembers he’s supposed to love your enemies and all that [stuff]. He says if he were to be frank, he can’t love his enemies. He can’t love those who hurt him without cause. He doesn’t just want God’s favor and mercy. He wants God’s vindication. He says, “I won’t accept anything less, even [despite] my hatred towards the ones who hurt me.” He’s also afraid to confess any of his pain, to talk to God honestly, bravely about the profound hurt and anger in his heart for fear that God will be angry toward him. Not only has he suffered physical and verbal abuse, but he has also suffered spiritual abuse. His need for justice, for vindication is also a need for healing, for wholeness. His wounds are deep and grievous and need care. He is in no shape to turn the other cheek.

I have no idea what it is like to be young and Black and male in this country. I have no idea what it is like to be transgender or queer or poor. I have no idea what it is like to live with chronic pain or with a disability. I have no idea what it is like to be oppressed. I have no idea what it is like to live with such pain and anger. Though it often does not serve any purpose to compare suffering, my wounds are not a result of the abuse of my identity, of who I am as a person. And I have privilege that affords me the resources for healing. The ability to love one’s enemies is connected to the time and space to heal, to transform pain, trauma, and anger into something we can live with, and there are too many people who have not had, who do not have what they need to heal from pain and trauma.

|

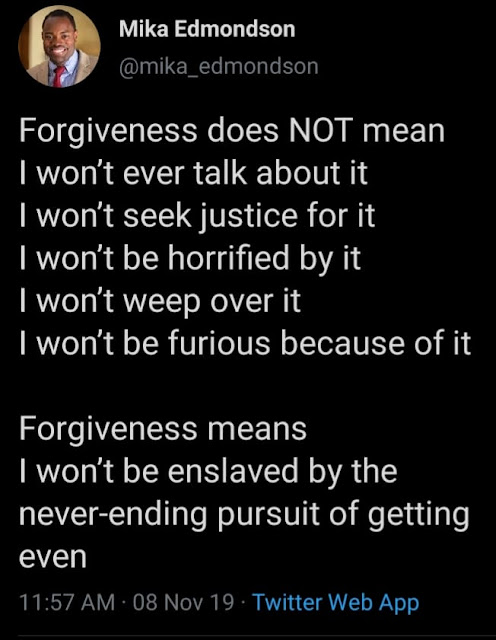

| Poem by Hana Malik from the collection RAW: How to Forgive "Forgiveness is/taking the knife out of your own back/and not using it/ to hurt anyone else/no matter how/they hurt you |

Anglican priest Rev. Daniel Brereton says that those who preach should preach from their scars and not their wounds. The same is true when it comes to loving our enemies. We can only love our enemies from our scars, not our wounds. Those who have been wronged and repeatedly so cannot be expected to love their enemies, to love and forgive from a place of pain and woundedness, a place of injustice. That only subjects those who are suffering to further injury, makes them vulnerable to those who wounded them, and increases their trauma.

If it is one thing the Church is called to do, it is to have compassion, to care for the wounded, especially those who have been wronged and excluded by community, those who are on the fringes of community, who have been hurt by community, including the Church. And yet if we are to be agents of healing, we need to attend to our own healing first. Lori Deschene, founder of the online community Tiny Buddha, writes, “Be the person who breaks the cycle. If you were judged, choose understanding. If you were rejected, choose acceptance. If you were shamed, choose compassion. Be the person you needed when you were hurting, not the person who hurt you. Vow to be better than what broke you—to heal instead of becoming bitter so you can act from your heart, not your pain.”

Poet Hana Malik wrote, “Forgiveness is taking the knife out of your back and not using it to hurt anyone else, no matter how much they hurt you.” Wound care is about not transferring our pain to anyone else, not using it as a force for revenge or power over others. If we cannot desire good for those who have hurt us, we can at least wish them no harm, not only for them but for our own good as well.

We live in a world permeated by trauma, generations of it, much of it ignored, devalued, and untreated. We live in a society that tells us to just move on and leave the past behind or keep the pain alive, in the present for as long as you can. Build monuments to your pain. Numb your pain. We are in danger of becoming the very thing we fight against. We would rather turn against each other than turn the other cheek. Jesus would rather we act from our heart, not our pain. Seek justice, yes, but not revenge. Weep and get angry and feel the sadness but not as a means of keeping wounds open as a source of power or control. We won't do this perfectly. It's messy and complicated. The awful, terrible, amazing thing about love is that it can both hurt and heal, it can make us vulnerable and strong, it is a weakness and it is a force, it can reduce us and it can resurrect us. Choose love anyway. Amen.

Benediction – Harold Warheim

Because the world is poor and starving,

Go with bread.

Because the world is filled with fear,

Go with courage.

Because the world is in despair,

Go with hope.

Because the world is living lies,

Go with truth.

Because the world is sick with sorrow,

Go with joy.

Because the world is weary of wars,

Go with peace.

Because the world is seldom fair,

Go with justice.

Because the world is under judgment,

Go with mercy.

Because the world will die without it,

Go with love.

Comments

Post a Comment